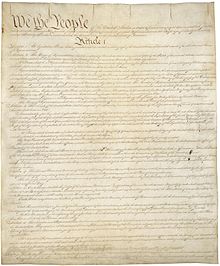

The "In GOP we Trust" image from Nate Hochman's Opinion Guest Essay, "What Comes After the Religious Right," in today's NY Times is hard to resist. But so too is his article and its argument the long-term decline of religious influence in "conservative political project," which "is no longer specifically Christian." None of that is or ought to be completely surprising, certainly to those motivated mainly by religious concerns who have watched with growing concern the increasing subordination of religion to right-wing identity politics in so many manifestations organized American Christianity in the United States today.

From a religious perspective, I think it is almost invariably the case that when religion becomes too preoccupied with attaining and/or maintaining political power, it is power that prevails while real religion recedes. History has confirmed this over and over - in the 20th century with the disastrous Catholic integralist regimes in Ireland and Spain, and in the 21st century with the political deformation of much of American Christianity as a result of increasing alliances with the Republican party.

A fellow at the conservative publication National Review, Hochman argue that it enjoys the electoral support of most Christian-identified Republicans, the new conservative coalition "is a social conservatism rather than a religious one, revolving around race relations, identity politics, immigration and the teaching of American history" and "focused on questions of national identity, social integrity and political alienation."

Demographically, he notes that self-identified Christians in the U.S. dropped from 75% in 2011 to 63% in 2021, while the so-called "nones" grew from 19% to 29%. Meanwhile, the percentage of Republicans who belong to a church went form 75% in 2010 to 65% in 2020. And, in that year, fewer than half of Republicans said "being Christian" was an important part of being American - a 15% drop in just the four years since Trump's election. Indeed, he directly associates the decline in Republican church membership with Trump's rise. The demographic at the heart of trump's base - what sociologist Donald Warren calls "Middle American radicals" (MARs) - "is composed primarily of non-college-educated middle- and lower-middle-class white people, and it is characterized by a populist hostility to elite pieties" but does not share traditional Cristian "moral commitments," in both "their political views" and "their lifestyles."

Hochman sees "the fierceness of today's culture wars" as "actually tied to the decline in organized religion." He cits Sam Francis' 1994 essay "Religious Wrong," which argued that cultural, ethnic and social identities “are the principal lines of conflict” between Middle Americans and progressive elites and that the “religious orientation of the Christian right" served "to create what Marxists like to call a ‘false consciousness’ for Middle Americans.” Francis, Hochman argues, saw Christianity’s universalism as at odds with the defense of the American nation, against mass immigration and multiculturalism. “Organized Christianity today,” Francis wrote in 2001, “is the enemy of the West and the race that created it.” One result, Hochman notes, is that "in the absence of a humanizing Christian ethic, white racial consciousness could fill the void."

One consequence of this change, Hochman suggests, is that "disaffected recent converts in the conservative coalition often object to the new left-wing puritanism for the same reason that they objected to its old right-wing counterpart: It prevents them from doing and saying whatever they please, free of social repercussions. That is its own kind of libertinism. Social conservatives, in contrast, do not oppose the enforcement of social norms as such; they oppose the enforcement of left-wing social norms on the grounds that they are the wrong norms." As a result, "old social conservatives will need to decide how much they are willing to concede in exchange for a political future, and secular converts will need to decide if they are more alienated by the left’s cultural authoritarianism than they are by the G.O.P.’s positions on issues like abortion."

The bottom line for Hochman is that this "new cultural conservatism may protect the embattled minority of traditionalist Christians; it will not restore them to their pre-eminent place in public life, as the old religious conservatism hoped to do."

No comments:

Post a Comment