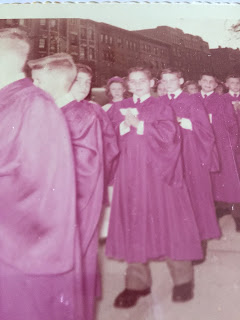

65 years ago today, I was confirmed. Confirmation is officially the second of the Catholic Church's seven sacraments, although in contemporary Catholic practice it is typically the fourth, perhaps one of the many mistakes we continue to make regarding this sacrament. In the above photo from my confirmation day in 1957, we were all in two lines (as we so often were in those days), wearing our Confirmation gowns (red for boys, white for girls) and holding our all-important name cards. I guess I was looking directly at some family member holding a camera - all the while very attentively guarding my name card. Whatever its theological and sacramental significance, I personally experienced confirmation primarily as just another life-cycle celebration, a "rite of passage" (a term with which I was then surely still unacquainted). Indeed, some years later at my 8th-grade Baccalaureate Mass, the priest referred to confirmation as "something that just happened to you when you reached a certain age" (in contrast to our graduation which, he suggested, represented more of an actual accomplishment on our part).

According to the Baltimore Catechism, question 330, which we faithfully memorized, "Confirmation is the sacrament through which the Holy Ghost comes to us in a special way to enable us to profess our faith as strong and perfect Christians and soldiers of Jesus Christ."

Whatever that actually meant may have been less than completely clear to me at the time. What was particularly important to me about my my confirmation was that I got to choose a confirmation name. I chose Michael for my confirmation name, because I was attracted by the bellicose militaristic image of Michael the Archangel in the prayer which we then regularly recited as part of the so-called “Leonine Prayers for Russia” recited after Low Mass. Because that was what I cared the most about, that is the part of the ceremony that I best remember.

Thus, when my turn came to kneel before the Bishop on his faldstool in front of the High Altar, a priest took the card out of my hand and announced my confirmation name to the Bishop (in what I would later learn was the nominative case). The Bishop then addressed me (in what I would later learn was the vocative case): Michael, Signo te signo crucis; et confirmo te chrismate salutis. In nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti. ("Michael, I sign you with the sign of the cross and I confirm you with the chrism of salvation, in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.") And that was it! Perhaps because we were so many, or perhaps because the Bishop was a foreigner, there were no Bishop's questions to terrify us. Once we were all confirmed, we recited some prayers together and left the church in the same orderly way we had entered (minus the name card). An irreverent observer (had there been any present) might have wondered what the fuss was all about.

At Mass earlier that day - unusually for that time, my Confirmation took place on a Sunday, so, of course, we had all attended Mass earlier that morning - an older student said "Congratulations" to me. I remember that I thanked her, although what about being confirmed quite warranted congratulations was not completely obvious to me either then or now, since it was, after all, "something that just happened to you when you reached a certain age." More accurately, of course, for most of history, Confirmation was something that happened to you when a bishop happened to be available. Hence we hear those marvelous stories of medieval villages lining up the local kids along the roadside to be confirmed on the occasion of a bishop riding by. But, in 1950s New York, there were plenty of bishops available, and so Confirmations occurred regularly according to a schedule that appeared to be determined by one's grade-level in school.

Thus, Confirmation seemed even then to be less of a big deal than the energy invested in it would seem to have warranted. For all sorts of reasons, we still manage to make a big deal out of Confirmation, but now in a different context in which fewer young people are likely to get confirmed. By continuing to celebrate it out of its proper order, moreover, we may give the impression to those who do get confirmed that confirmation is the sacramental culmination of Christian initiation, instead of the Eucharist. Not only does that distort the relative importance of those two sacraments, it burdens Confirmation with an obligation it seems hardly equipped to fulfill.

Back in 1957, however, my Confirmation was just another part of a way of life sanctified by the building in which it occurred. It was that great gothic-towered parish church, that dominated the neighborhood both physically and socially, that took me out of time and beyond the narrow confines of my limited space, and that taught me that to go to the altar of God would give joy to one’s youth. (Introibo ad altare Dei, ad Deum qui laetificat juventutem meam, as we were then happily taught to say.) That was something wonderful, which remains with me to this day!

No comments:

Post a Comment