The ordinary guy, of whom little is expected, of whom nothing extraordinary is ever expected, until he does the opposite, is a familiar figure in history, literature, and life - think Abraham Lincoln, or Ron Weasley in Harry Potter, and - most relevant right now - embattled Ukraine's heroic President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. The hero of the hour is young (44) and, until relatively recently, that is, prior to becoming a president, was a performer, a comedian, who danced with the stars and played a president on TV. Now he is a real president, the leader of a nation at war, and performing better in that role than most of his critics (and perhaps even his fans) might have expected.

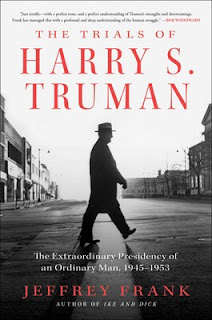

In the 20th century, the classic exemplar of that traditional trope of the ordinary man of who little was expected but who turned out to be an extraordinary leader, was Harry S Truman, the 33rd President of the United States. My father was a great admirer of President Truman, and at least one element in his admiration of Truman was that Truman had never gone to college. I always assumed Truman was the last U.S. President not to have gone to college. From Jeffrey Franks's new book on Truman, The Trials of Harry S. Truman: the Extraordinary Presidency of an Ordinary man, 1945-1953 (Simon and Schuster, 2022), I learned that Truman was the only president never to attend college, Like the period after the "S" in Truman' name, I think that may be a mistake on the author's part. I don't think George Washington ever attended college. (There were only two in British North America at the time, and Washington never traveled to Europe.) But the basic point remains. Everything about Truman and his background and previous accomplishments was ordinary and unpromising as a predictor of the great president he proved to be.

And Truman had the added disadvantage of replacing Roosevelt! Frank relates the familiar anecdotes about how, when Truman entered the East Room for FDR's funeral service, no one stood, because, so it seemed at the time, those there “could not yet associate him with his high office; all they could think of was that the President was dead.”

Frank starts his story with a quote from Roy Roberts of the Kansas City Star, "not a Truman admirer," who "was struck by the idea that someone who not so long before 'was still looking at the rear end of a horse' should find himself leading the world’s most powerful nation. 'What a story in democracy,' he wrote, and added, 'What a test of democracy, if it works.' What a test indeed."

Like Frank, I think,Truman clearly passed that test - and with him democracy - despite what we might label his cultured despisers, such as those Washington "insiders," for whom "the very idea of Harry Truman as the nation’s leader was so off-putting."

That said, it does not follow that ignorance and inexperience are virtues to be lauded as what we commonly call "populism" seems to suggest. Franks himself noted Truman's limited knowledge and how. in the first test of Truman's international leadership, the Potsdam Conference, his provincialism was disastrously on display. But Truman was, as Churchill described him "a man of immense determination," who "takes no notice of delicate ground, he just plants his foot down firmly on it." And, just weeks after his unexpected accession to the presidency, Dean Acheson said of Truman that, despite “the limitations upon his judgment and wisdom that the limitations of his experience produce,” he believed that “he will learn fast and will inspire confidence.” Above all, Frank notes, Acheson judged Truman to be “straight-forward, decisive, simple, entirely honest.”

Frank takes us through Truman's almost eight years in the presidency. He highlights Truman's attraction to "the sociability of politics" and the problems that could result at times from that. We see Truman's complexities, for example, his almost [populist disdain for elites, combined with his reverence for someone like General George Marshall. We are taken back to the critical early days of the Cold War, when the pressure to bring American soldiers home was overwhelming, but so was Truman's recognition of the growing and seemingly inevitable threat of Soviet expansionism, which required a new dominant power to replace the depleted British and French empires. Of course, the atomic bomb gets attention - both its use to end the war successfully and then its perennial presence in the background of all subsequent conflicts, especially the largely disastrous Korean "police action."

Not unlike contemporary politicians, Truman suffered from the swings of popular opinion - from the catastrophic midterm elections of 1946 to Truman's amazing comeback in 1948. All the major high points are covered - the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan, the Berlin Airlift, the 1948 turn to civil rights and the resultant Dixiecrat walkout, Israel, Korea, Joe McCarthy, General Mac Arthur, the steel strike, the 1952 election and the quarrel with Eisenhower - comprehensively revisiting "a time that was contentious and dangerous, triumphant and tragic."

As Republican Senator Vandenberg said of Truman on the morning after the 1948 election. “You’ve got to give the little man credit. Everyone had counted him out but he came up fighting and won the battle. He did it all by himself. That’s the kind of courage the American people admire.”

No comments:

Post a Comment