Just as generations and decades have become increasingly popular - if pointlessly arbitrary - markers, much that same might be said for the infamous "First 100 Days" by which we insist on judging our contemporary presidents. When Franklin D. Roosevelt became president on March 4, 1933, the country was in shambles; and it was FDR's decisive leadership in his first 100 days and the special session of Congress which met during that time that dramatically uplifted the nation's spirits and started the country on the road to recovery - and in the process provided pundits and others with this pointless but popular measure of every new Administration.

Joe Biden may be the first president since FDR to inherit a country as comparably devastated - above all by the global pandemic and its manifold consequences, all exacerbated by four years of misgovernment by his predecessor. So the impetus for immediate, decisive, and dramatic action is similar, which may make the "100 Days" less an arbitrary journalistic gimmick than it would normally be. Certainly, as in 1933, the country is in crisis and has ousted one president and elected a new one in the expectation that the new president will make a difference in ways his predecessor had failed so ignominiously to do.

And Biden has not disappointed. On the eve of his 100th day, our second Catholic President and thus the most prominent and influential American Catholic, addressed the Congress in a sort of unofficial "State of the Union." He gave his address in an unusually semi-empty House Chamber, with only about 200 people present and without the usual extraneous guests in the gallery, in order to exemplify Covid precautions. There was an added strangeness to this, in that - thanks to the Administration's success in getting so many Americans vaccinated - such precautions may soon be ancient history. One hopeful benefit of the smaller audience, however, was that there were fewer opportunities for Republicans to engage in childish silliness and misbehavior. It also, of course, highlighted how the speech was being actually addressed directly to the rest of us. (At least since LBJ started giving State of the Union Addresses in the evening instead of at noon, Congress has long been more of a prop than the main audience on such occasions anyway.)

The strange setting also enabled the President to highlight the unique "crisis and opportunity" that is, effect, the state of our union right now.

The speech celebrated the many amazing accomplishments already achieved in the first 100 days and challenged Congress to act - to argue and debate but above all to act. At the end, he articulated the overarching question: Can democracy deliver? And he challenged Congress and the American people all to "do our part." The speech was Roosevelt-like in inspiration. (Indeed, his closing words were reminiscent of Eleanor Roosevelt's Pearl Harbor day radio Address in 1941.)

It was good - for the first time in many decades - to hear a President speak like a traditional Democrat and friend of the working class (in other words, neither Clintonian neo-liberalilsm nor woke progressivism). It was refreshing and encouraging to throw away - hopefully for good - the destructive government-is-not-the-solution Reagan playbook that has undermined this country for the past 40 years.

There remains, however, one important difference between FDR in 1933 and Biden in 2021. While FDR's actions altered and transformed America, Biden has so far, for the most part, mainly proposed to do so. His proposals would likely change an America desperately in need of transformation - on as significant a scale as FDR and LBJ's legislative accomplishments. But, apart from the already passed and monumentally significant ARP, most of Biden's agenda has yet to be enshrined in legislation. And, like LBJ, he has only until next year's election to get that done. The reality remains that the Democratic Party's hold on Congress is so fragile that caution and moderation serve no purpose, nor do obsessive appeals to a long-gone chimerical bipartisanship. The goal at this point must be to accomplish whatever one can, as much as one can, as quickly as one can, before the likely loss of congressional control in 2022 puts a virtual end to all domestic legislation, while in fact the only possible hope to avoid that 2022 loss would be to have actually accomplished a lot that actually makes a difference in people's lives and can drown out the obsessive nihilism of the culture warrior opposition.

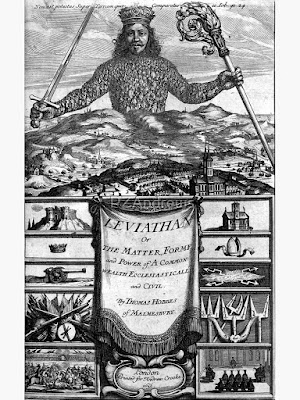

(Photo: President Biden addresses a joint session of Congress on the eve of his 100th day in office, as Vice President Harris and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi stand behind him on the dais. Melina Mara/Pool/Getty Images)