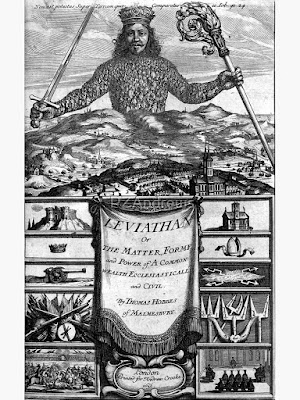

The famous frontispiece of the 1651 edition of Thomas Hobbes' classic masterpiece Leviathan (photo) shows Hobbes's sovereign, sword in one hand, scepter in the other, whose power provides peace and order to the community pictured below. Yet as Sheldon Wolin wrote some 60 years ago: "The sovereign's powerful body is, so to speak not this own; its outline is completely filled in by the miniature figures of his subjects. ... Equally important each subject is clearly discernible in the body fo the sovereign. The citizens are not swallowed up in an anonymous mass, nor sacramentally merged into a mystical body. Each remains a discrete individual and each retains his identity in an absolute way" [Politics and Vision: Continuity and Innovation in Western Political Thought, (Little, Brown, 1960), p. 266]. That famous image speaks volumes about the individualistic, non-communitarian language and political premises we Americans have inherited from Hobbes and the early modern Liberal tradition.

Despite dire threats to public safety and public health, contemporary American society seems stymied by anti-social elements that oppose the public and common good - with a purported "right" to private ownership of deadly weapons, with a purported "right" not to wear masks in public, with a purported "right" to refuse to be vaccinated against a deadly disease that has spread all around the world and has claimed more than half a million American lives alone in this past year.

Obviously, anyone at all acquainted with the distinctive history of the United States and with the language of the Declaration of Independence is familiar with how highly valued the idea of individual "rights" is in our society's self-understanding - and how its prominence sets us apart from other Western democratic societies. Individual "rights" and reasoning based on such assumptions are so pervasive that even critics of this tradition's consequences sometimes seem at a loss for words with which to counter it.

And for a long time, of course, there were any number of pre-modern, non-individualistic communal institutions (e.g., families, churches) and other communitarian networks which persisted as healthy antidotes to the extreme individualism of orthodox "rights" language. Such residual elements of an earlier outlook and pre-modern social arrangements - what Karl Marx in his Grundrisse called "partly unconquered remnants" of "vanished social formations" - by their persistent presence and survival into relatively recent memory may have helped soften individualism's cutting edge, providing arrangements of sociability which individualism itself can never provide.

Surely the preservation of viable families, churches, and other communitarian networks and, to whatever extent possible, their recovery where they have already been diminished or have disappeared would be a beneficial alternative to our thoroughly fragmented present reality. All indications, however, question whether such solidarities can be salvaged in a society in which they have been increasingly strangled by the suffocating excesses of individualism. As the absurd arguments about guns, masks, and vaccines illustrate so poignantly, individual "rights" removed from any social reference and responsibility destroy any sort of solidarity and reduce everything to fantasized self-interest.

The traditional American fascination with John Locke (1632-1704) notwithstanding, it was Locke's immediate forerunner, Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), who first formulated in an important way our modern notion of individual "rights" - distinguishing between right and law, defining right in terms of liberty and law in terms of obligation. Hobbes' picture of politics, in which political order was a pure product of rational calculation, cannot appear unfamiliar to an American. It is an artificial alliance formed and based upon individuals for the most satisfactory attainment of their essential private, personal interests. While the calculation that created a necessary political arrangement obviously has rearranged the external environment, it aspires to leave our moral characters as unaltered as possible. We remain socially and politically compromised. Our purposes remain the products of our passions, and our reason remains no more than rational calculation. We will cease to be or really never become citizens in a properly political sense. We are hardly even friends - except in the rather qualified and incidental sense of friendship Aristotle ascribed to those who are so on the basis of utility [cf. Nicomachean Ethics, VIII, 4, 1157b]. The inability to foster in people the kind of commitment to the common and public good which would cause them to embrace the burdens and benefits of citizenship points to the politically problematic dimension of defining ourselves in terms of our individual "rights," while the more general inability to instill and cultivate a capacity to care for one another indicates the socially problematic dimension of defining ourselves in terms of our individual "rights."

Hobbes had created his Leviathan state to clamp a lid on the conflicts which would be inevitable between and among "rights"-bearing individuals. Our own American Leviathan state (so much more powerful in practice than anything Hobbes could have actually envisaged in his time) has instead lifted the lid, allowing ever increasing inventions of individual "rights" and ever increasing advocacy on their behalf, increasingly unrestrained either socially or morally by whatever remains of "vanished social formations." The consequence, however, is (to appropriate Hobbesian imagery) a kind of continuation of a state of war within civil society. The more the protective armor of "rights" is employed, the more seemingly inevitable is the persistence of conflict and the more inconceivable any alternative sensibility which would hopefully facilitate a transcendence of conflict.

Hegel somewhere said that weapons are but the essence of the combatants themselves. As citizens armed with "rights," Americans have become the antithesis of friends, hence hardly citizens at all. Friendship, Aristotle argued, "seems to hold states together." Friends, Aristotle also argued, "have no need of justice, but when they are just, they need friendship in addition" [Nicomachean Ethics, VIII, 1, 1155a].

Sociability, fostered by friendship, would hopefully help polarized Americans rediscover citizenship and overcome the perennial problem of inequality and other divisions. Needless to say, individual "rights" remain as much a symptom as an agent of division. Eliminating the language of individual "rights" would not, in and of itself, recover the language, let alone the reality of common citizenship, of shared responsibility for the public and common good. But we must begin somewhere, if we are to reconsider our relationships with one another and rediscover what it means to be human together.

No comments:

Post a Comment