Sometime back in the 1980s, one of my seminary classmates ventured the opinion that the Easter season, as we now have it, is simply too long and should be confined to one week (in other words, to the existing Easter Octave). His argument, if I recall it correctly, was that it was just too difficult to sustain so much enthusiasm for seven long weeks. Certainly, in our contemporary world of radically reduced attention spans combined with our current addiction to celebration by anticipation (e.g., the way we celebrate Christmas before December 25 rather than starting on December 25), it seems our current seven-week Easter season is problematic. (In this discussion, I am, of course, completely prescinding from the obvious fact that, for many people, probably none of this matters at all. In a modern secular world, where religion itself, let alone liturgy, barely impinges upon the ordinary routines of life, whether it is Easter Time or, say, Advent, may matter much less than religious professionals would like to imagine.)

In any case, our current seven-week Easter season is itself a relatively recent construct, dating back only to Pope Saint Paul VI's 1969 calendar reform. "The fifty days from theSunday of the Resurrection to Pentecost Sunday are celebrated in joy and exultation as one feast day, indeed as one 'great Sunday'" (Universal Norms on the Liturgical Year and the Calendar, 22). This post-conciliar Easter season certainly recognizes some diversity within it - the Octave of Easter, Ascension Day, and the nine "weekdays from the Ascension up to and including the Saturday before Pentecost." But the prevailing tendency of the reformed calendar (evident even more so perhaps in its treatment of Lent) was to flatten such internal seasonal diversity in favor of a unified, somewhat monochromatic conception of the season as a whole.

Thus, for example, one of the most commented upon features of the contemporary version of the Easter season is the replacement of the traditional collects of the (themselves renamed) Sundays between Easter and Pentecost. The traditional collect for "Low Sunday" famously spoke of having completed the paschal festivities (paschalia festa peregimus), while those of the subsequent Sundays said nothing specific about Easter at all. This was seen as a serious problem by the liturgical bureaucrats charged with revising the Missal, and those collects have all accordingly been replaced - perhaps the best evidence of the intention to establish a uniformity in the Easter season over the seven-week period.

Of course, the old Paschaltide (like the current Easter season) had certain distinctive features that perdured uniformly throughout the entire time, notably the numerous alleluias, the Regina Caeli, and the Vidi Aquam. But, then as now, apart from the octaves, an ordinary saint's day took precedence over a ferial day. (In practice the ferial Mass was seldom celebrated anyway, yielding as in most of the rest of the year to the then much more popular Requiem Mass.)

That said, the current Easter season's predecessor seemed to take a more realistic, less uniform approach to sustaining prolonged celebration. Thus, the pre-conciliar Paschaltide, which ran from the beginning of the Mass of the Easter Vigil to None of the Saturday within the Octave of Pentecost, was explicitly defined to include a distinct season of Easter, a season of Ascension, and the Pentecost Octave. The difference between the Easter and Ascension seasons within Paschaltide was dramatized best by the requirement that the Paschal Candle, a symbol of the uniquely paschal presence of the Risen Christ, be solemnly extinguished after the Gospel at the Mass on Ascension Thursday and then removed from the sanctuary. Nowadays, of course, the paschal candle keeps reappearing all year (at baptisms and funerals, for example, and in many places where the baptistery is not really separate from the main body of the church it remain visible all year long). So the fact that it remains an extra 10 days after the Ascension may not seem so counter-symbolic as it obviously is. (Then again, I once witnessed the Paschal Candle ceremonially extinguished after the Gospel on Pentecost, an even more symbolically confusing conflation of old and new. Hopefully, no one went home imagining that it was the Pentecostal tongues of fire that were being extinguished!)

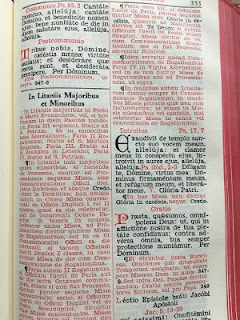

In addition to the major variations already mentioned, the traditional Paschaltide also included the "Lesser Litanies," that is, the three Rogation Days" on the Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday before the Ascension. (In Milan, they were more logically celebrated on the Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday after the Ascension.) And the Octave of Pentecost included the summer Ember Days, somewhat contradicting the ancient notion that there should be no fasting during the Easter season.

But, other than celebration fatigue and the shortened attention span problem already alluded to, perhaps the difficulty resides not so much in the desire to sustain celebration for too long a time as in the flattening of that same time by the downgrading of Ascension and Pentecost. Along with Christmas and Epiphany, the feasts of Easter, Ascension, and Pentecost are the five principal festivals of the liturgical calendar, still distinguished as such in the Roman Canon and previously distinguished by Octaves. There is a certain logic to dividing "the 50 days" into an Easter 40 and an Ascension 10, not least in order to correspond with some fidelity to the biblical account. The modest reference in the present arrangement to the weekdays between Ascension and Pentecost as ever so slightly set apart from the rest of the season represents a minimalistic vestige of that division. In the absence of an Ascension octave, treating Ascension Thursday (obviously always on Thursday) as the end of the specifically Easter season, followed by a nine-day period of preparation for Pentecost would be one way of making sense of the season.

That still leaves the problem of Pentecost and its now lost octave. Whether due to the reformers' apparent antipathy to octaves in general and to an overly literal obsession with the number 50, the destruction of the Pentecost octave can only be seen as a (presumably irreparable) loss. According to the familiar story, when Pope Paul VI went to vest for Mass on the day after Pentecost in 1970, and found green vestments laid out for him, he asked "Where are the red vestments?” He was told that the Octave of Pentecost had been abolished. “Who did that?” he supposedly asked, only to be told “Your Holiness, you did.” And so the story concludes, the pope wept. Whether true or apocryphal, the story does express the damage done to the liturgy by the gratuitous abolition of the Pentecost Octave. More recently, Pope Francis has made a small gesture to correcting that mistake by instituting the Memorial of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of the Church, to be celebrated always on the Monday after Pentecost.

Restoring a sense of Easter not as a uniformly flat time but as a season with several (specifically three) peak moments might help to retrieve Ascension and Pentecost as feasts truly celebrating the beginning of the Church's current life.

Meanwhile, on the ground in the real world of contemporary American religion, the peak moments of the otherwise flattened Easter season will continue to be First Communions, Confirmations, Graduations, maybe May Crownings, and the biggest American pseudo-religious commercial feast of all, Mother's Day.

(Photo: Easter 1963, St. Nicholas of Tolentine Church, Bronx, NY)